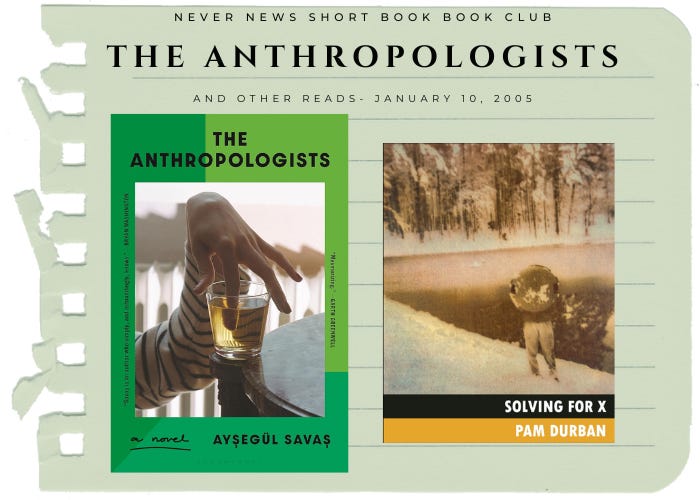

For the Never News Short Book Club, Colin reads novels under 250 pages each week; readers are encouraged to read along at their own pace and check back when they’re ready. Paid subscribers get to vote on the books read each month. This month’s book is: Ayşegül Savaş’ The Anthropologists.

When my partner and I found each other, the connection was instant. It seemed obvious, even in the early and unsteady days of our courtship, that we were committed for the long haul. It wasn’t anything that we had ever experienced before, and it wasn’t something we discussed much (aside from all the sappy declarations of love); it also wasn’t easy.

Not long into our relationship, she got accepted into graduate school half a country away from our little Wyoming city, which immediately locked us into a two-year long-distance relationship. After a brief period of living together for the first time, three years into our relationship, we moved across the country together; two years later, we moved again.

It’s been hard, through all those changes, to find a sense of permanence outside of one another. Our friends and family now geographically distant, each new place meant finding new routines, new places, new people, and new habits. It sometimes feels alienating and frustrating to no longer have a built-in social circle; it was hard, even, to find the restaurants we most liked, the places we could build small, comfortable rituals within.

We’ve both lost parents, in that time, and a friend; major events in the lives of those dear to us have gone by without our being there. We aren’t quite part of the community in our current city, and even though we bought the house we’re living in, there’s an air of impermanence — it still feels, despite our commitment (to the place, to one another), to be a long-term lease.

There is a looming threat of impermanence in Ayşegül Savaş’ The Anthropologists, a feeling that laying down roots does not prevent the slippage of time, that feels overwhelmingly familiar and moving to me. Though the novel’s central young married couple, Asya and Manu, are foreigners in their home city (and from different cultures from one another), I couldn’t help but identify with their struggles even if they spanned the globe.

Throughout the novel, they struggle with establishing and keeping hold of the constants of life: family, friends, home. These things seem just outside of reach: their friend Ravi is the heart of their social community of three, but even his presence is not guaranteed. Asya’s grandmother, like the old woman who lives upstairs, is suffering the slow decline of the elderly.

Most importantly, Asya and Manu are attempting to find a permanent apartment, a place to buy that will cement them in this place even if their social and familial reasons to settle are evaporating around them.

For all that, it’s a sweet novel, a book intent on examining these hardships but not burdened by them; for all the small concerns of place, the inner reality of Asya and Manu’s marriage is a place of almost divine and banal loveliness. This isn’t a book where we witness a marriage struggle, it’s a book where we recognize the secret language of couples.

Describing one of their small rituals — the burning of sage — Asya thinks to herself that “. . . this was the great relief: that we did not consider each other strange.” In passing, she discusses how ‘Manu and I graduated and began forming our own mythology.”

Which is to say that, for all the trouble of being isolated and unsteady, the permanence of their lives is in their shared strangeness, their own stories. It’s hard to see the bedrock when the landscape shifts so imperceptibly.

This novel has a sort of earnesty that would be embarrassing from a more cynical standpoint, which made it all the more believable — and valuable — to me. It’s a comfort to someone who has, for the last ten years or so, been focused on the anthropological study of alienated, paired adulthood. ★★★★⯨

There’s a much more pressing sense of impermanence in Pam Durban’s Solving for X . Durban, 77, puts forward four short essays in the volume, and each of them deals with the sort of housekeeping of loss that comes at the end of life.

It’s a warmly tragic collection, because the subjects Durban writes about — late-life memory loss, her husband’s dementia, her brother’s terminal illness — are, of course, inevitable; Durban turns her immaculate considerations to them as painful, necessary concerns. There is loss, here, but it’s expected. It feels like a countdown clock to her own mortality.

‘. . . I still want more because life ends, but wanting more never does,’ she writes, and nothing feels so earnest of a feeling than that. This is a book about aging, about losing mental and physical autonomy, of grieving about things that aren’t yet — but must soon — be gone.

I hadn’t read Durban before this; after picking up and reading a handful of issues of Inch from Bull City Press a couple of months ago, I was so smitten by the project (micro chapbook quarterly, one writer per issue) that I immediately subscribed.

And thank God I did, because this Winter issue arrived and it’s a doozy. I feel an urgent need to experience more of Durban’s work, which is so clean and resonant. I’m very fond of these little volumes, and now I’m likewise fond of the writer. ★★★★⯨

This week at AIPT: