It is, of course, an inherently futile endeavor for a man as white as me to attempt to comment, with any degree of clarity or insight, on the racial concerns portrayed in a novel written one hundred years ago by a black woman. (Very brave hot take: racism is bad.)

That doesn’t mean, of course, that I did not take a lot away from Passing by Nella Larsen — the first of her I’ve read (there isn’t much more — another novel and some short stories, all of which can be obtained in a single volume) and, tragically, only my third or fourth excursion into the incredible Harlem Renaissance of literature.

I loved Passing; there’s something about early- and mid-century American Lit that is so sumptuous and satisfying to me — all that lovely prose, prim and proper but not dense, immensely readable. Larsen was a contemporary of Langston Hughes, of course, but also F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald and (thought not stylistically similar) Gertrude Stein; it’s not far removed from Anaïs Nin. This is a novel coming out of the roaring twenties, adjacent to the Lost Generation, and subject to the linguistic mores and habits of the time.

Sure, those habits are dated — we’ve moved away from the proper and the ornate and decided, somewhere around the 1970s, that literature needed to be more naturalistic and conversational, and while I don’t disagree with some of those tendencies I still crave a novel like Passing, which reads so melodically and elegantly that it feels almost impossibly lush for a book so small. A lot is going on in here, and it’s not just the racially covert ramifications of “passing” or the warm and inviting look at that high tide of Harlem cultural affairs. Even the book’s shocking, Gatsby-like ending doesn’t sum up the depth of the writing. The book’s protagonist, Irene, has such a rich inner life, and we know that because every line of prose feels doubled in its content.

The sad truth is, for as much as I love prose in this style, I’m critically under-educated not just in the Harlem Renaissance but in the larger history of American Lit; I dropped out of college with a half-dozen writing workshops under my belt and barely any of the hardcore surveys English majors are meant to take, and when I went back to school in my thirties, I went to a liberal arts school where I crafted my own reading list.

The thing is, a novel like Passing wasn’t what was being taught in colleges for a long, long time of academic thinking; there has long been a concern surrounding the Dead White Guys framing of education, and I’m thankful to have dodged that somewhat concerning indoctrination. Though a strong and steady course through college would have had me reading more Hemingway and Faulkner, it would not have me reading Nella Larsen.

I wasn’t exactly supplanting that structural understanding with writers like Larsen or James Baldwin; I was off reading then-contemporary literature and a whole lot of post-war favorites (I wouldn’t be who I was or write what I write without a healthy dose of JD Salinger and Shirley Jackson). This era — outside of the obvious entries — is a blindspot that I intend to illuminate; that journey will likely be tracked here, in this column that twenty or so people are reading.

As with so many books I’ve been reading, the pile grows rather than shrinks as soon as I complete something. I’ve got the complete Nella Larsen bibliography on my reading device now. Nearly every writer I’ve read since rebooting Never News has been shuffled into a to-do list I will likely never complete. ★★★★☆

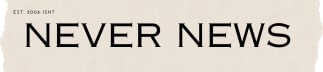

January’s Never News Short Book Club:

01.10.25 - The Anthropologists by Ayşegül Savaş

01.17.25 - Passing by Nella Larsen

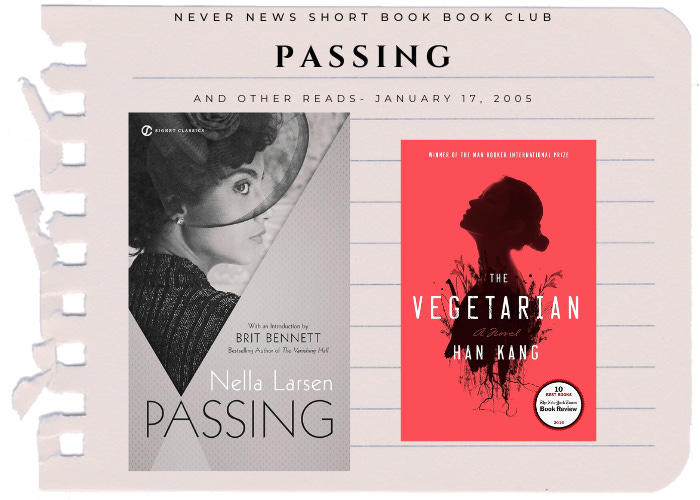

01.24.25 - The Hawkline Monster: A Gothic Western by Richard Brautigan

01.31.25 - The Aspern Papers by Henry James

Han Kang is on that very same endless to-do list, though much further down the line. It isn’t that I didn’t enjoy my time with The Vegetarian, but I spent most of my time with the novel wanting to put it down and research the implications of Korean culture on the narrative. I would love, for instance, to find a lengthy critical essay centered around the novel that would fill what is lacking in my knowledge of that particular cultural history.

Because that’s what the barrier is: a failing of my own. Literature in translation should do exactly this: drive the reader’s curiosity and open their receptiveness to the foreign. The trouble is that my curiosity cannot always grapple with the constraints of time and come out on top.

The book is deeply compelling, and packed with memorable characters (all of whom are terrible); the central and titular character is such a confounding conundrum of a character, however, that I sometimes felt as if I was misunderstanding her journey and purpose. Her horrifying wasting away — physically, mentally — felt like it was coded in some way that I was having trouble deciphering. Was there a bit of rebellion there? Was this a reaction to a violently patriarchal situation? Was there something to the sexual violence and the sexual embrace? What did this mean to the other characters?

Why flowers? Am I dumb?

This doesn’t mean that I won’t try to better engage with Han Kang’s writing: she’s got a new book out at the end of this very month that sits on my list of upcoming books I’d love to get to at some point in the coming year. The only way to learn is to do; the only way to understand a writer is to read them. ★★⯨☆☆

My work this week on AIPT:

Reading this week: